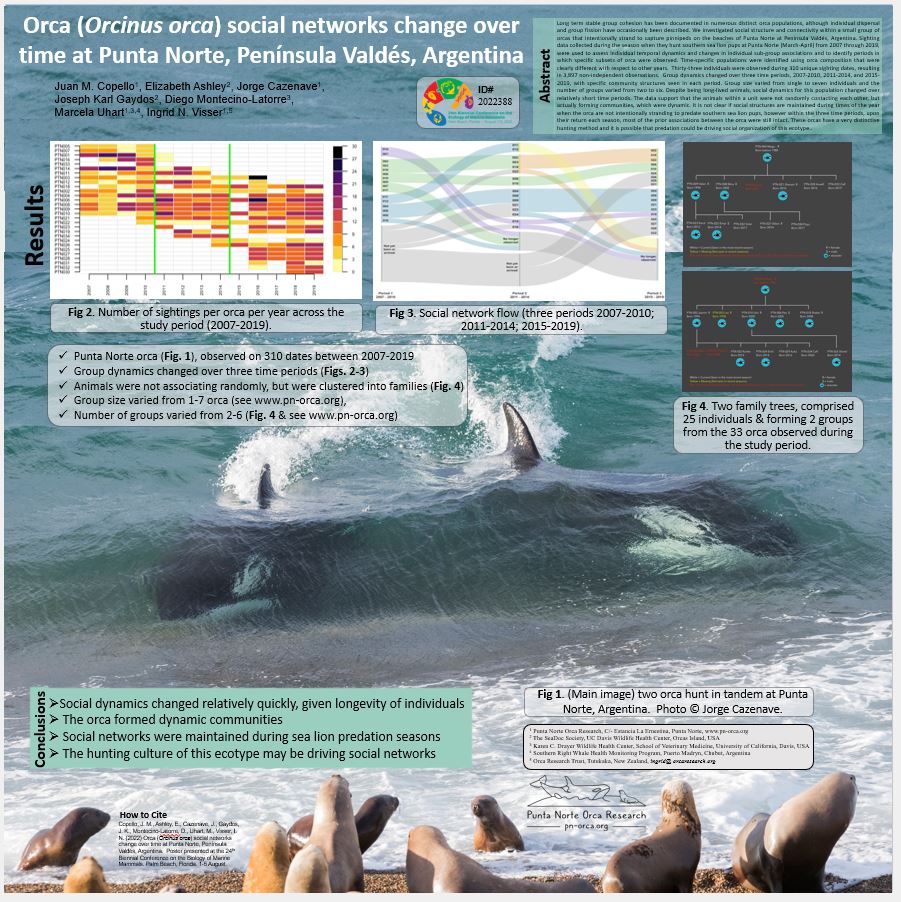

The Society of Marine Mammalogy scientific conference was held 1-5 August 2022 in Florida, USA. Four members of the PNOR team attended virtually and co-authored this poster, which can be downloaded as a pdf.;

Copello J.M., Asheley E., Cazenave J., Gaydos J.K., Montecino-Latorre, Uhart M. & Visser I.N. (2022). Orca (Orcinus orca) social networks change over time at Punta Norte, Península Valdés, Argentina. Poster presented at the 24th Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals; 1-5 August; Palm Beach, Florida.

Although social networking has really only come into the forefront of our awareness in recent years, we have been doing it since we first started evolving. So too have all the other animals, yet the complexities of social animal species have only recently begun to be studied, with research on the social networks of orca only being conducted in the last few decades. The importance of understanding social networks lies at the individual level (e.g., which animals spend time with others) but it also has implications at a population-wide level (e.g., how are genes being spread throughout the species).

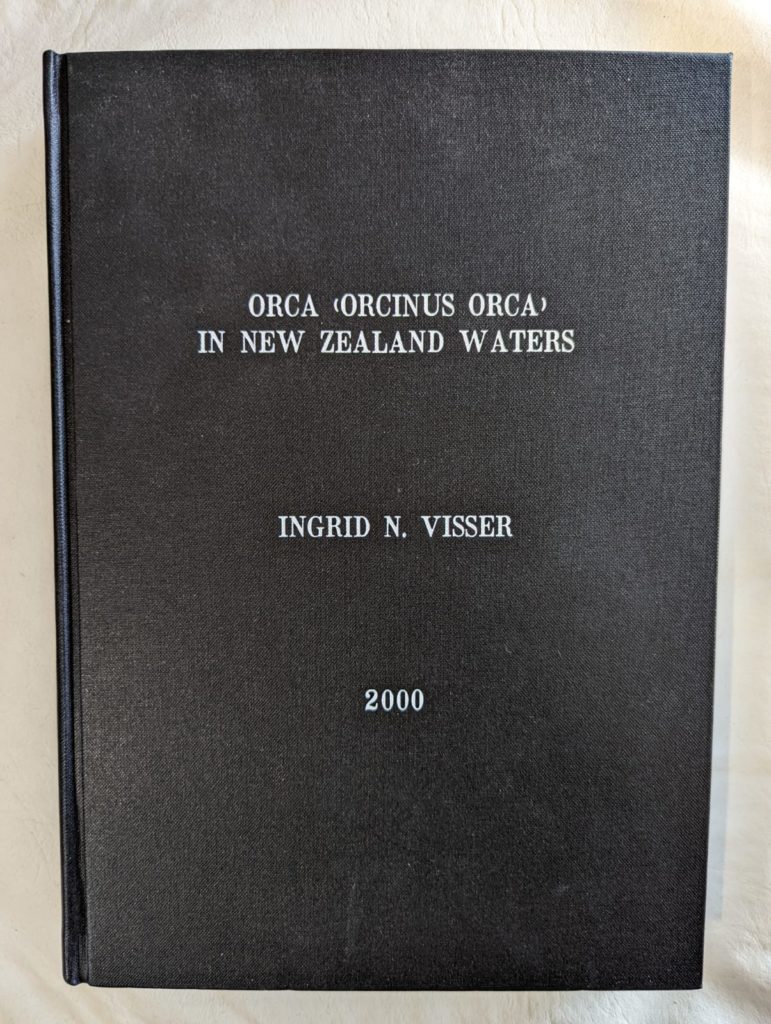

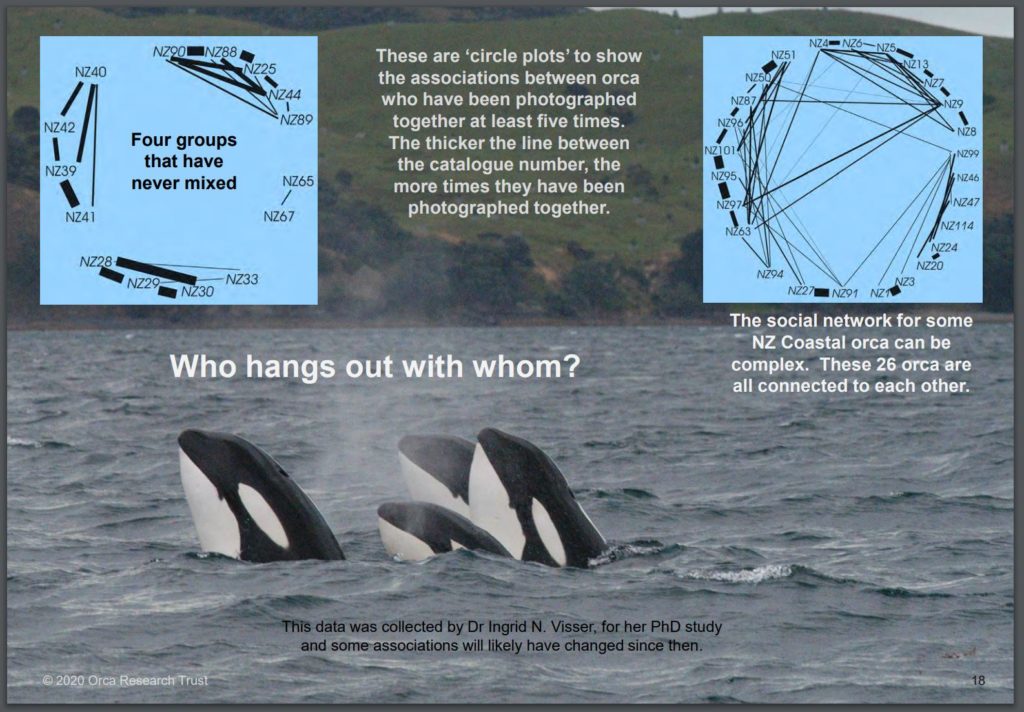

Most studies on orca social networks have focused on a ‘snap-shot’ approach – even if the data is gathered over time, a single portrayal of the network is typically described. For example the research by Dr Visser documented the associations of NZ Coastal orca over a period of years. However, as individuals were at times not seen for a year or more, the data was very patchy and it wasn’t possible to look at really fine-scale association information. Additionally, she was documenting the same orca as they travelled to a range of locations throughout New Zealand. But during these years and across these locations Dr Visser was able to look at the number of times an individual was seen with another (i.e., pair associations, also known as dyads) and the number of times each individual was seen with the others in the group, as well as it it’s total number of ‘contacts’. This showed that there were at least two discrete populations; one was very interconnected and the other had tightly formed groups that rarely, if ever, interacted. She used ‘circle plots’ to show these levels of interconnectedness (and lack of it!) – and these are included in the NZ Orca ID guide which can be downloaded from by clicking on the picture below:

If you want to read the details of the study, you can download Dr Visser’s PhD by clicking on the picture below;

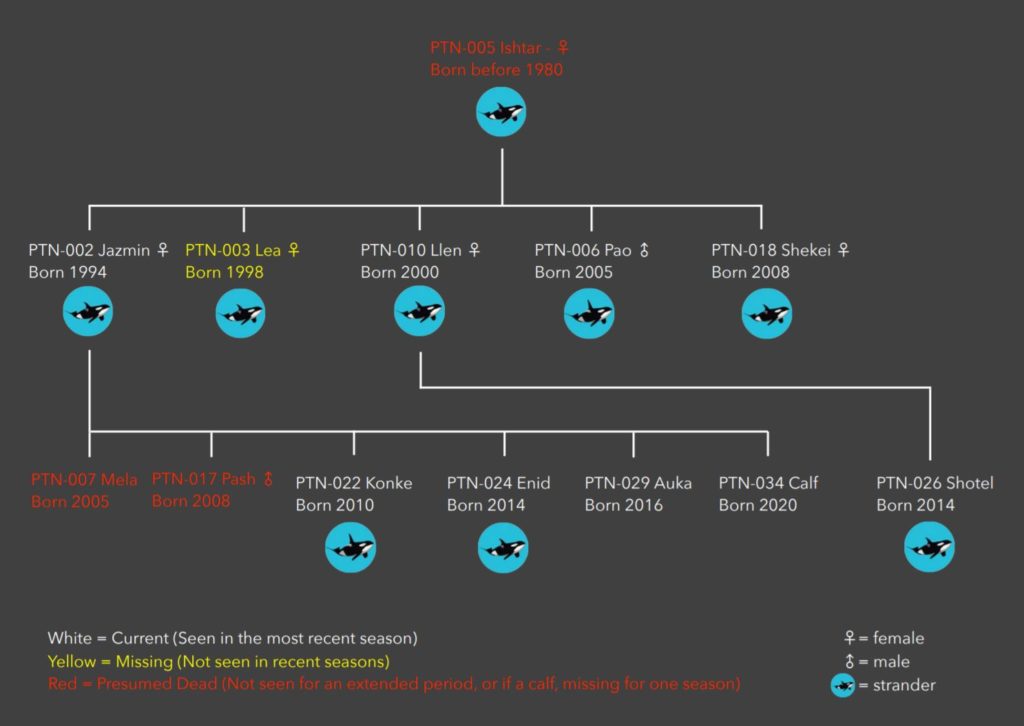

Another way to look at social networks is to look at the changes over time, but that takes a lot of data, preferably collected at the same time each year (so as to remove any seasonal influences, such as you find with humpback whales who travel to warmer waters in winter). Together with my colleagues at Punta Norte in Argentina, we have gathered social networking data for the past 16 years on the Punta Norte ecotype of orca, during the sea lion hunting seasons (Feb-April). During each season, although there are periods where the individuals show up on an almost daily basis, at times they might not show up for a few weeks. But with us based in just one area of this immense coastline and at the same time of year, we can eliminate that the location or season is impacting any changes in the data that we gather. This has enabled us to assess the data using a ‘river’ or ‘flow’ association network that better illustrate the complexities of a social network over time. Individual assocations, family associations and population-level associations all help us better understand these complex social animals.